The 2010 Smiley Award Winner: ámman îar

I am very pleased to present the 2010 Smiley Award to ámman îar, a personal language of enormous breadth and wondrous creativity, constructed by David Bell. Mr. Bell is no longer with us, but this recognition is long, long overdue. Congratulations, David!

http://graywizard.conlang.org/amman_iar.htm

A True Tolkienian Conlanger

Many conlangers can trace their conlanging history to one of two sources: Esperanto or Tolkien. While it's quite evident that David Bell hailed from the latter camp, he was far from your average Tolkienite. While he too shared Tolkien's sense of aesthetics ("I too love the sound of 'cellar door'," he writes), what intrigued him most was Tolkien's contention that a language needed a world behind it to be a true, "living" language. It was this that led him to imagine his "Blessed Land", ámman, which he intended to populate with languages and peoples. Over the course of forty odd years, he did just that. Though most of his work remains in his own personal files and notebooks, he did share with us his crowning conlinguistic achievement: the language ámman îar.

A Cut Above

There is a stereotype (which is as true as most stereotypes [i.e. quite true until you start to examine the data]) amongst conlangers regarding those who are influenced by Tolkien. Generally these are teenage conlangers who fall in love with elves, hobbits and dwarves, and who want to create a "new" world that's just like Tolkien's (replete with knights, rangers with names suspiciously similar to "Legolas", and races that are very, very close to Tolkien's original beings [e.g. "ints" for "ents"]). When they encounter Tolkien's languages, then, they try to do the same thing, copying Quenya and/or Sindarin in every detail, but, say, changing the ablative ending from -llo to -mmu, or the rough equivalent thereof, thereby making something "original".

On the surface, it might appear that David did the same thing with ámman îar. If you look at a random smattering of words (aldar "tree", Anariel "a woman's name", garassar "town", ilorvinil "last"...), they certainly do sound

A System to Be Reckoned With

Those of us who've been connected to the conlanging community for ten or so years know that even we conlangers are susceptible to trends. For example, at one point in time, everyone was coming out with a new language featuring Celtic consonant mutations. Then it was "trigger" systems. Then it was minimal languages. Then it was visual languages. Tomorrow it'll be something entirely new (meaning something that was probably done ten years ago). But without a doubt the single biggest trend in all of modern conlanging history was ergativity. Everybody and their left-handed Lithuanian uncle tried their hand at creating an ergative language (yes, even me). It might not be surprising, then, to learn that David Bell, the Tolkienian conlanger, created an ergative language in ámman îar.

What is surprising, though, is how good it is.

Of course, it should be noted that ámman îar predated the ergative trend (in fact, its introduction to the conlanging community may even have started it), so in that context, it's not as surprising to learn that its system is well constructed and well planned.

As I noted in my ergativity reference page, no natural language is purely ergative (though, as far as I know, the jury's still out on the fascinating stuff going on in Australia). Conlangs that otherwise appear quite naturalistic tend to tip their hand with an ergative system that's far more pristine than any natural language would ever allow. David Bell's ámman îar, far from falling into the trap of artificiality, features a wonderfully balanced split ergative system that a linguist wouldn't be surprised to find in the wild. Take a look (this table is adapted from David Bell's site):

| Semantic Role | 1st/2nd Person Pronouns | 3rd Person Pronouns/Demonstratives | Other Nouns | |||

| Inflection | Case | Inflection | Case | Inflection | Case | |

| A | - | NOM | -e | ERG | -e | ERG |

| S | - | NOM | - | NOM/ABS | - | ABS |

| P | -in | ACC | -in | ACC | - | ABS |

A few comments on this system before moving on. The pattern shown above derives from an animacy hierarchy inherent in the language. Arguments are broken down into three basic categories: First and second person pronouns; third person pronouns and demonstratives ("this one", "that one", etc.); and then other nouns, including proper nouns (i.e. names). This is a hierarchy one sees often in natural languages, but rather than simply copying it, David spells out the rationale behind it. A marker, he reasons, denotes the

The hypothesis or generalization that drives the marking system, shall we say, holds that entities of higher animacy are more likely to act as agents in a transitive construction. With first and second person pronouns, then, the result is a fully nominative/accusative system. It's expected that a first or second person pronoun would be the agent in a transitive construction; it's unexpected that it would be a patient. Therefore, the patient is marked. With third person pronouns and demonstratives, it could go either way. The special accusative marker -e is used to highlight the fact that a third person argument (pronoun or otherwise) is acting in a highly animate way. On the other hand, third person pronouns, being more animate than common nouns, are marked with the accusative case when acting as patients, to note their relatively low animacy. And so, across the full range of nominal arguments, there's a full nominative/accusative system, a full ergative/absolutive system, and a tripartite system—and just two suffixes.

Added to this is the fully ergative nature of the syntax (in coordination constructions, for example, it's the absolutive argument that carries over, not the ergative), and the active predicate inflection system to complicate matters. The result is a wild web of interrelated inflection that's quite marvelous to

- életh eni dais orgöirar. "The tiger died." (Intransitive verb, patient-like subject.)

- i dais ergabdhel életh. "The tiger pounced." (Intransitive verb, agent-like subject.)

- i daisse életh an thoren erechöiron. "The tiger killed an eagle." (Transitive verb, agent and patient.)

- (életh) eni dais thorenen henîarth. "The tiger saw an eagle." (Transitive verb, patient and theme.)

- i daisse életh in thoren erhenîel. "The tiger looked at an eagle." (Transitive verb, agent and theme.)

There's a lot that can be gleaned from these examples, so let me try to summarize (it'll help to illustrate the layers of redundant inflection):

- The placement of the auxiliary verb, in effect, marks the most patient-like argument of the sentence, which it always precedes (when there is none, as in 2, it follows the verb; also, the auxiliary is optional in 4).

- Case marks the grammatical roles of each nominal argument. (In these sentences, we have only nouns, which means the alignment is ergative. The ergative suffix can be seen in sentences 3 and 5 [i daisse as opposed to i dais].)

- There are verbal markers to denote the semantic roles of the verb's arguments. A verbal prefix er- is used when an agent or agent-like argument is present. In intransitive constructions (including those with extra theme arguments), the patient or patient-like argument is preceded by the preposition en (which often absorbs a following definite article i). This preposition surfaces as an when an agent and patient are present, and as in when an agent and some other theme is present.

- If that weren't enough, an -a suffix is added to intransitive verbs with a patient-like subject; an -e suffix is added to intransitive verbs with an agent-like subject; and before each of these an -i suffix is added if the otherwise intransitive verb adopts an additional thematic argument. For true transitive verbs, with an agent and patient, the suffix is -o.

- Plus, word order is not free: Subjects precede objects (both direct and indirect), and agents and themes precede patients.

That's five different layers of marking spread out across not just the verb complex, but the entire clause. This is a masterful system David

Other Highlights From the Blessed Land's Lingua Franca

I love awarding the Smiley, because it gives me a chance to fully explore a language that previously I'd seen and liked, but perhaps not gone through with a fine-tooth comb. In looking over ámman îar, I found a number of things I'd glossed over in years past that jumped out at me.

For example, take a look at this adjectival system, which, for lack of a better term, I'm going to classify as an "adjective noun class system" (I guess that's probably just an "adjective class system", but for some reason that doesn't sound right...). All adjectives are preceded by a prefix which describes the type of adjective the word is (the content not being enough). He has the following list on his adjectives page:

| Class | Prefix | Semantics | Example |

| Descriptive | ve- | Describes what the noun is like. | riel vemarlis "beautiful woman" |

| Purposive | pa- | Describes what the noun is used for. | tornil pamurmlir "sleeping bag" |

| Material | ge- | Describes what the noun is made from. | teleg galdar "wooden leg" |

| Size | ma- | Describes how big or small the noun is. | caras mabeleg "large house" |

| Color | de- | Describes the color of the noun. | curunar demith "gray wizard" |

| Shape | ta- | Describes the shape of the noun. | palag tacom "round table" |

| Count | be- | Describes how many of the noun there is. | lhibai becaer "ten fingers" |

| Age | la- | Describes how old the noun is. | cair lorseinnon "ancient ship" |

| Origin | ha- | Describes where the noun comes from. | sinair harhun "eastern manners" |

Okay, I'll be the first to admit that this list is a little one-to-one, and one wonders about the particular categories chosen, but isn't the idea awesome?! One can imagine varying adjectival stems (or verbal or nominal stems, for that matter) each of which can take different adjectival class prefixes to create different senses. And, if one is working with an adequately expansive period of time, one can easily imagine how the system would erode, producing new unanalyzable roots that still look similar due to the old system. I tell you, this idea is at the top of my list of conlanging ideas to steal borrow and then implement!

Something quite similar in spirit to the adjectival system is the genitival system, shown below (the original is here):

| Type | Semantics | Example |

| Alienable Possessive | Describes an alienable possession relationship. | vir'authnar megil "warrior's sword" | Inalienable Possessive | Describes a permanent possession relationship. | cem i vardilan "Mardil's hands" |

Subject Genitive | Describes a subject-like relationship. | narn ir ægnorannîon "Ægnor's story" |

Object Genitive | Describes a object-like relationship. | ordagar i garasso "the city's destruction" |

Partitive | Describes a part/whole relationship. | tilig i balagûo "the table's legs" |

Measure Genitive | Describes a measurement relationship. | andar i rathîo "the road's length" |

You'll notice that this is a nominative/accusative-aligned genitival system. What fascinates me is that this system focuses not on the type of relationship, per se, between the two nouns, but on what role the possessor plays in the

I was also pleasantly surprised to find that David actually covered naming traditions in ámman îar. It's probably not something that comes up everyday when conlanging or dicussing conlangs (which is probably why I didn't notice it until recently), but it's one of those things of which I'm fond. The ámman îar system is quite interesting. Each individual has four names:

- endar nerrion: A name chosen by a child upon reaching maturity (age 16).

- endar andirrion: A given name chosen by a child's parents at birth.

- endar edairrion: The endar narrion of a child's parent of the same sex (boys take their father's; girls, their mother's).

- endar atharrion: The father's clan name.

His description goes on further to specify exactly how different people of varying ages and social status refer to one another (so, for example, an adult will use the endar andirrion of a close friend, but with someone with whom they are unacquainted, they'll use a combination of the endar andirrion and the endar edairrion). To give you a full example, David Bell's ámman îar name is:

curunaran demith meldon îanannîon athar calonothîon

Gray Wizard David (i.e. beloved) son of John of the Bell Clan

(And, yes, in case you're curious: Our name does mean "beloved" in...some language.)

Finally, I'd be remiss if I didn't mention how well-organized David's site is. Everything is laid out in table of contents format (like a webified version of a print reference grammar), all subsections properly marked and interlinked, and he had the most thorough method of presenting translations with interlinears that I have ever seen. Here's an example taken from his site of the translation and interlinear of sentence 5 from the second section above:

i daisse életh in thoren erhenîel The tiger looked at an eagle. i dais -e eleth in thoren er heno -ie -l . A=AGT :ERG PAT P=REF AGT :AGT/REF :ACTN. the tiger did eagle see .

Line by line, he gives you: the sentence in its full ámman îar form; the smooth English translation; the morphophonemic breakdown (including the basic forms of each root and affix); the relevant labels for the roots and affixes; and, finally, their

How ámman îar Has Made Me Smile

Heh. Check this out:

![]()

Periodically throughout his site, David will include this little gray pointing finger to point out an important fact that may have been missed. I always found it annoying (as if he were saying, "Ah, ah, ah! Pay attention!"), but looking back, it's quite amusing. In fact, I chuckle to myself every time I see it now.

You see, in addition to the Smiley Award, I've spent a good chunk of time taking David's old site (or what's still left of it at Archive.org) and moving it to its new home at graywizard.conlang.org. He used some ancient website creation software to create it, so updating it (and downloading and reuploading hundreds of images, and replacing all the accented characters with their hexadecimal equivalents) and moving it has taken a lot of time and effort. In doing so, you kind of get to know someone. After all, this was more than just David's conlang site: It was his everything site. As I've been working with it, I've learned a lot about him.

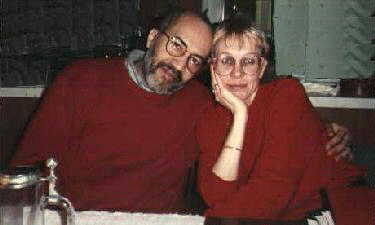

I noticed, for example, that David paid a lot of attention to the problems linguists have faced over the years. You can see its effect on his work. It's no coincidence that he's translated sentences like "the city's destruction", or "Luthiel's picture (of himself/of someone else/that he drew)". I noticed that, when it comes to noun and verb people, he's definitely a verb person (compare this page on noun cases to this one on auxiliary verbs [and that's just auxiliaries!]). And the word for "beautiful" I made reference to in a table above, marlis, is based on the name of his wife, Marlis Hundertmark Bell.

David's death, unfortunately, was the second time he was lost to us. He left the conlanging community several years ago, much to our detriment. Even so, he continued to work on his language and his website (parts of his table of contents that weren't linked to because they weren't finished had actually been finished at a later date). He took his work very seriously, and was quite justified in doing so. A lot of time and thought went into not just his language, but also its presentation. A conlanger's work is never finished, it's true, but I still can't help but feel that ámman îar came to a close too soon. Though described quite fully, there are large sections at the end of David's reference grammar that remain unfinished—and, perhaps the largest and most ambitious section, his lexicon, was barely begun (take a look at the entries for A as an example. A completed ámman îar lexicon would have been astonishingly rich and prodigious). And I haven't even made mention yet of his other languages...

Though we'll never hear from David again in this world, his work will be preserved, and his memory shall remain. I was sorry to hear he'd passed, because I felt he had more to say, more to offer... But wherever he is now (perhaps in that land beyond the sea), I'm sure he's happy. I wish this recognition (or something like it) could have come while David was still with us, but time has a way of getting away from us. At this point, this is the best I can do.

Congratulations, David! You will be missed.

David Bell

1942-2007